Photography by Christopher Niquet

Author

Jaja Hargreaves

Published

February 03, 2025

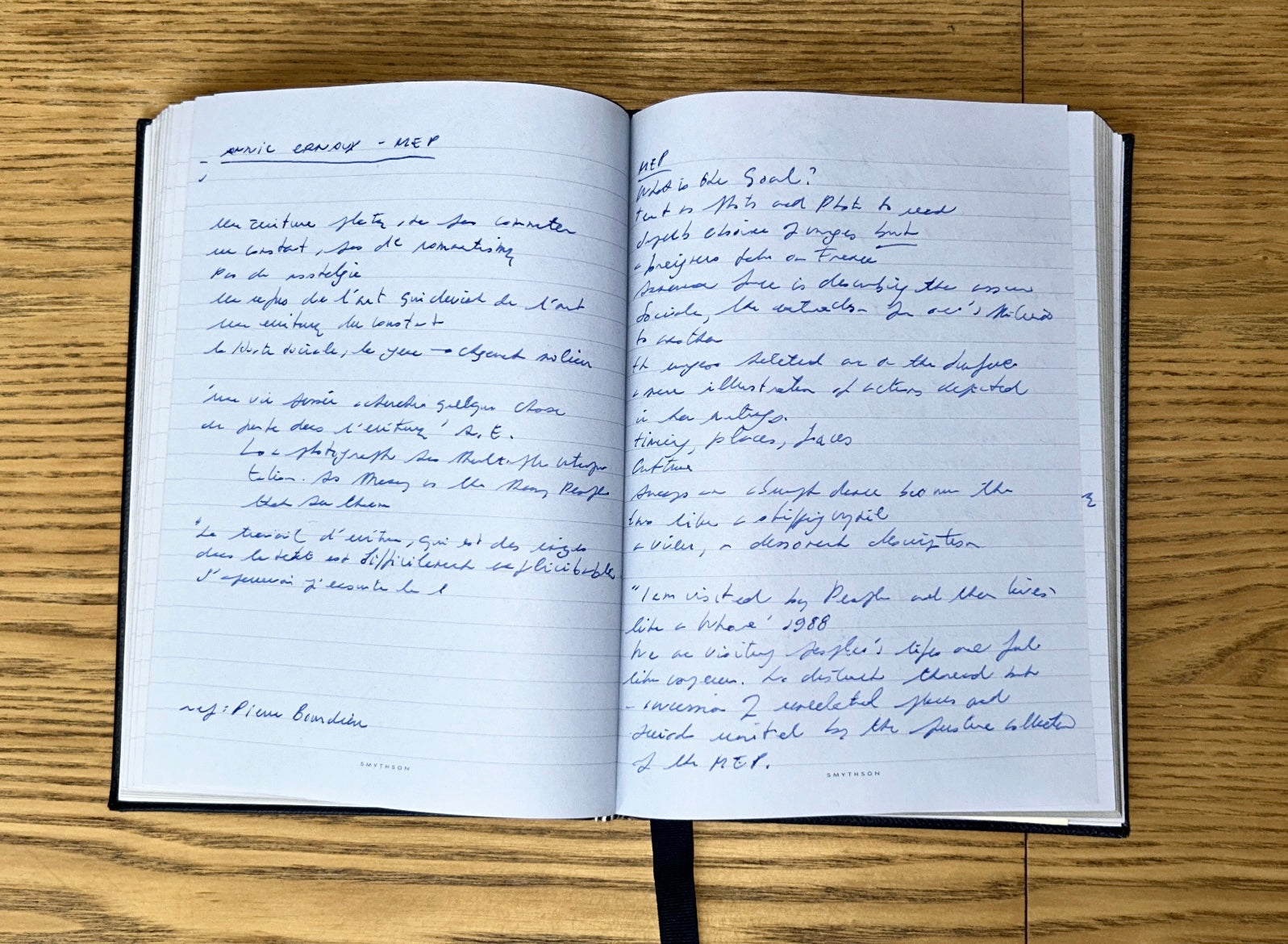

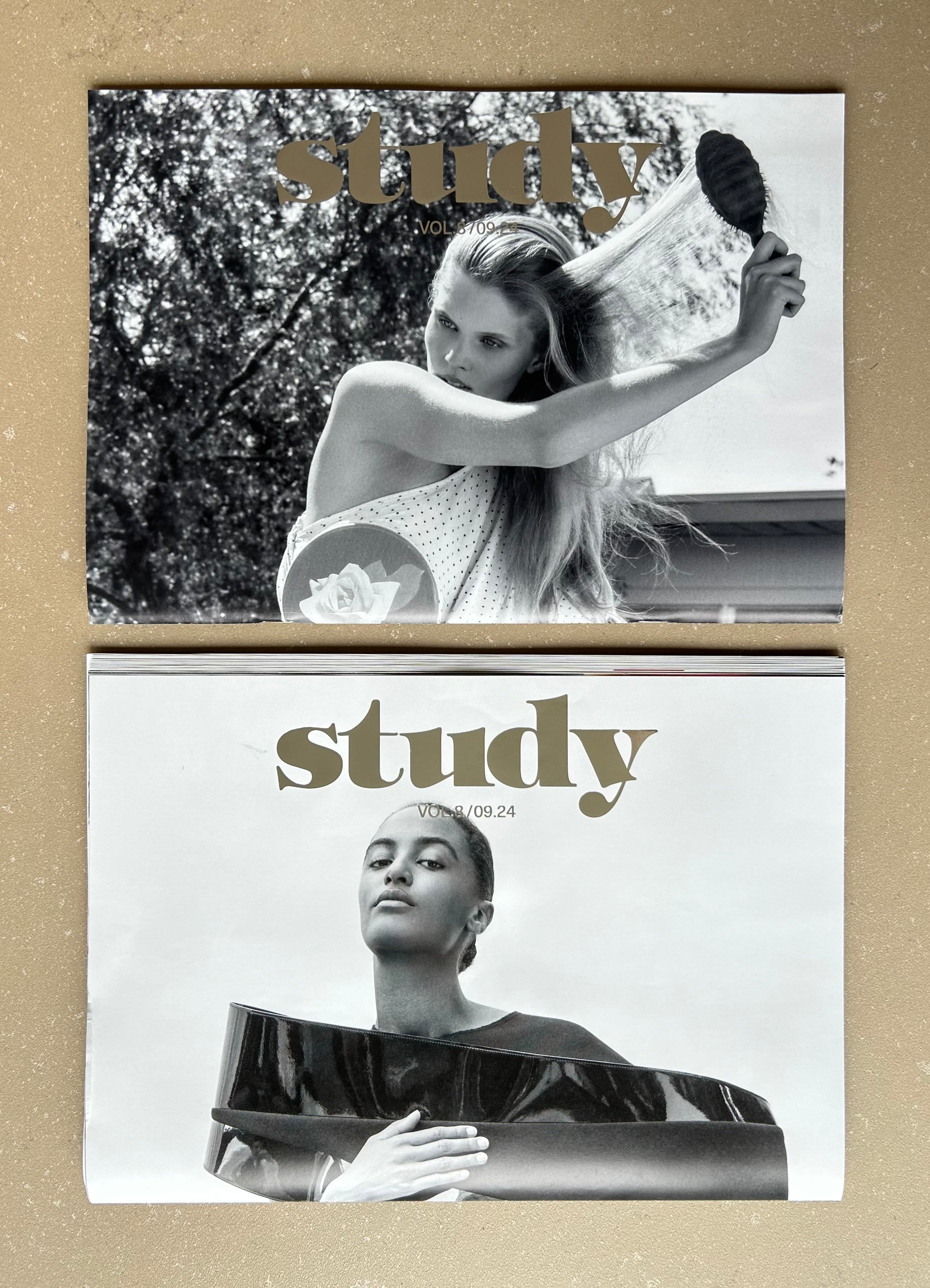

Christopher Niquet’s world feels both precise and expansive. Since 2022, his magazine has resisted the rush and fleeting nature of much of today’s media. Instead, STUDY offers something rare: depth. Each issue is dedicated to the work and life of one person; past subjects have included the stylist Camille Bidault-Waddington and the playwright Adrienne Kennedy. Through this mode of granular attention, STUDY invites its readers to slow down, and to notice the unexpected.

STUDY could be said to be a reflection of Niquet’s own journey. From his early years as a stylist in the fashion industry—working with the likes of Karl Lagerfeld and Christian Lacroix—to launching the magazine, he has always been drawn to the specific, the singular. Twinned with this, his approach has never been about chasing the moment, but about curating something lasting.

Niquet’s perspective is grounded in a time when creativity felt more tactile. Now in a digital era in which content is often ephemeral, his vision feels like a quiet rebellion. “Maybe right now mainstream media feels that it needs to cater to short attention spans and tell stories a certain way, but that’s not the direction I want to take,” he says. “STUDY is meant to be just that—a study. And to learn something, you need to dedicate time to it. I want my readers to spend time with the publication, not just consume it and forget it once they’ve closed it.”

Here, Niquet reflects on the pull of lasting ideas, the ever-changing creative landscape, and what it means to stay true to oneself as the world accelerates around us.

Each issue of STUDY focuses on one figure. What led you to develop this distinctive format, and how do you choose each issue’s subject?

I was often frustrated by the limited space allocated to the pieces that I wrote for other publications. I always found that I ended up wishing for more room to tell the story in a fuller, more complex way. I would also get annoyed when, in pitching multiple ideas, my favourite topics weren’t selected. That’s how STUDY was born. I wanted to build a publication around the things I truly cared about, while also being able to give them as much space as I believed they deserved.

How does your background as a stylist inform the editorial direction of STUDY?

This is my first foray into editing, so I don’t think my previous career as a stylist really influences STUDY. I never truly loved being a stylist; I kind of fell into it as a way to make money, and I kept at it until I no longer enjoyed it. There were good moments and great encounters—I loved being on set and watching an image come to life—but I don’t think I took much away from it, except maybe how to be collaborative, diplomatic, and solve problems quickly.

In the age of social media and a saturated magazine market, how do you keep STUDY unique and engaging for your readers?

I don’t overthink what I’m going to do in an issue; I trust my instincts. Social media has taught me that no matter how niche your interests seem, there are thousands of others who share them. So, instead of trying to please everyone, I dive fully into one topic and explore it in the way that feels right to me. I just assume each issue will find its readers, and this usually proves true, which is extremely rewarding.

Photography by Christopher Niquet

I’m guided solely by my taste and curiosity

Given that each issue might appeal to a different audience, how do you approach building a loyal readership? Is STUDY cultivating a following based more on curiosity than consistency?

I absolutely believe that the common denominator of our readers is curiosity. “Volume One” was centred around the Swiss model Vivienne Rohner, then our second issue focused on the American playwright Adrienne Kennedy. So we went from something highly visual to something more literary and substantive. I know it confused readers at first—Vivienne’s issue sold out fast, while Adrienne’s took longer—but I don’t mind that.

I’m always working on at least three issues at once, and I make a point of ensuring that each issue is as unique as possible. I’m aware that if an issue touches on style, it will sell faster, but that doesn’t deter me from exploring other subjects. Based on the data, our readers now buy issues regardless of the theme, which is really satisfying. They're willing to take a chance and discover something new each time.

How do you decide whose legacy to spotlight? And how important is it to you that STUDY contributes to these figures’ cultural significance?

I’m guided solely by my taste and curiosity. I just know when something will make a good issue, whether it’s something or someone lesser-known who deserves a wider audience or a major figure that I want to present in a new light. As for the impact of an issue, I can’t say—I think that’s something only time will reveal. STUDY is only two years old, so we’re just at the beginning of our journey.

How do you define legacy in the current fast-paced, digital world, and how do you think STUDY contributes to creating a lasting impact?

I could have made STUDY a digital experience, but I don’t think scrolling has the same effect as turning a page. To get to STUDY’s content, you have to open its packaging and extract the magazine, which is unbound and peculiar to manipulate, so you also have to be seated. All these choices were made to slow down time and make sure the reader is fully focused before consuming our content. The digital world is no longer new, and you can find high-quality content there, but I just don’t believe you can tell stories the same way on a screen as you can on paper.

Photography by Christopher Niquet

I still love the process of putting an issue or book together

In the case of, say, Adrienne Kennedy, a relatively cult but deeply influential playwright, you’ve chosen to highlight a figure whose impact hasn’t been fully acknowledged by mainstream culture. Do you see STUDY as an opportunity to rewrite cultural histories?

I’d start by saying that Adrienne Kennedy’s lack of acknowledgment in mainstream culture is solely because she’s a Black woman. There’s no other reason. As for STUDY being a tool to rewrite history, that’s not how I see it. Everyone I’ve dedicated an issue to has a body of work spanning decades and has been influential in their field, but maybe they’ve been too true to themselves to achieve mainstream relevance. Their work is specific and not for everyone.

I think that creative work often comes back to our teenage obsessions. Do any of the themes or subjects you explore in STUDY connect to the things you first fell in love with as a teenager?

I started interning in publishing as a teenager because I was obsessed with magazines and wanted to know how they were made. To this day, I still love the process of putting an issue or book together. My teenage years before magazines were about school, books, and horse riding. I still enjoy some of the authors I was reading then, like Marguerite Duras, and Allen Ginsberg, and I still love watching horse jumping competitions. The one thing that’s really stayed with me is my love for texts that are sharp and not too wordy.

You’re a stylist, editor and writer. Do you feel more closely connected to any one of these roles, or do they all intersect in a way that defines your creative identity?

Styling was something I fell into and stopped doing a few years ago. I wouldn’t want to return to it, but doing it for so long gave me an appreciation for stylists who have a real gift with clothing—when it’s done right, it’s like a language. With writing, I love it, but I always feel that I’m chasing something, and I get frustrated a lot. It takes me a long time to be happy with a piece. Editing, on the other hand, is the one thing I know I’m truly good at and enjoy doing. I know I can look at a piece of writing, a book, or a portfolio of photographs and move things around to make it better. That’s the skill I know I have, and it’s what I love doing the most.

Photography by Christopher Niquet

I have no nostalgia for the past

Did you have a creative childhood, or was there a particular moment or experience that sparked your love for the arts?

Not necessarily. I had a very normal French childhood, with parents who didn’t work in creative fields. Of course, I grew up going to museums, visiting castles, and attending the theatre, so I was exposed to cultural things. But I wouldn’t say I have a deep love for the arts—I’m just curious about things.

There’s a sense of nostalgia in your work. How do you feel about the rapidly advancing digital world, with AI and other technologies reshaping creative industries?

I have no nostalgia for the past—I don’t believe the world was better before. I love the moment we’re in now, and I would never give up my iPhone or laptop. I love that technology allows my graphic designer to be in Berlin, me in Paris, and most contributors in New York, while our printer is in Latvia. None of this would have been possible 20 years ago. I love the possibilities that technology offers—I think it’s about using the right tools for the right brain.

Is there a book you often gift?

The two books I’ve gifted most are Letters to a Young Poet by Rilke and The Year of Magical Thinking by Didion. Rilke’s book is a great one to give young people—it’s almost a rite of passage as they enter adulthood. Didion’s book is about grief, and I’m at a point in life where friends are starting to lose family members, so I feel it’s a fitting book to offer during those times.

Photography by Christopher Niquet