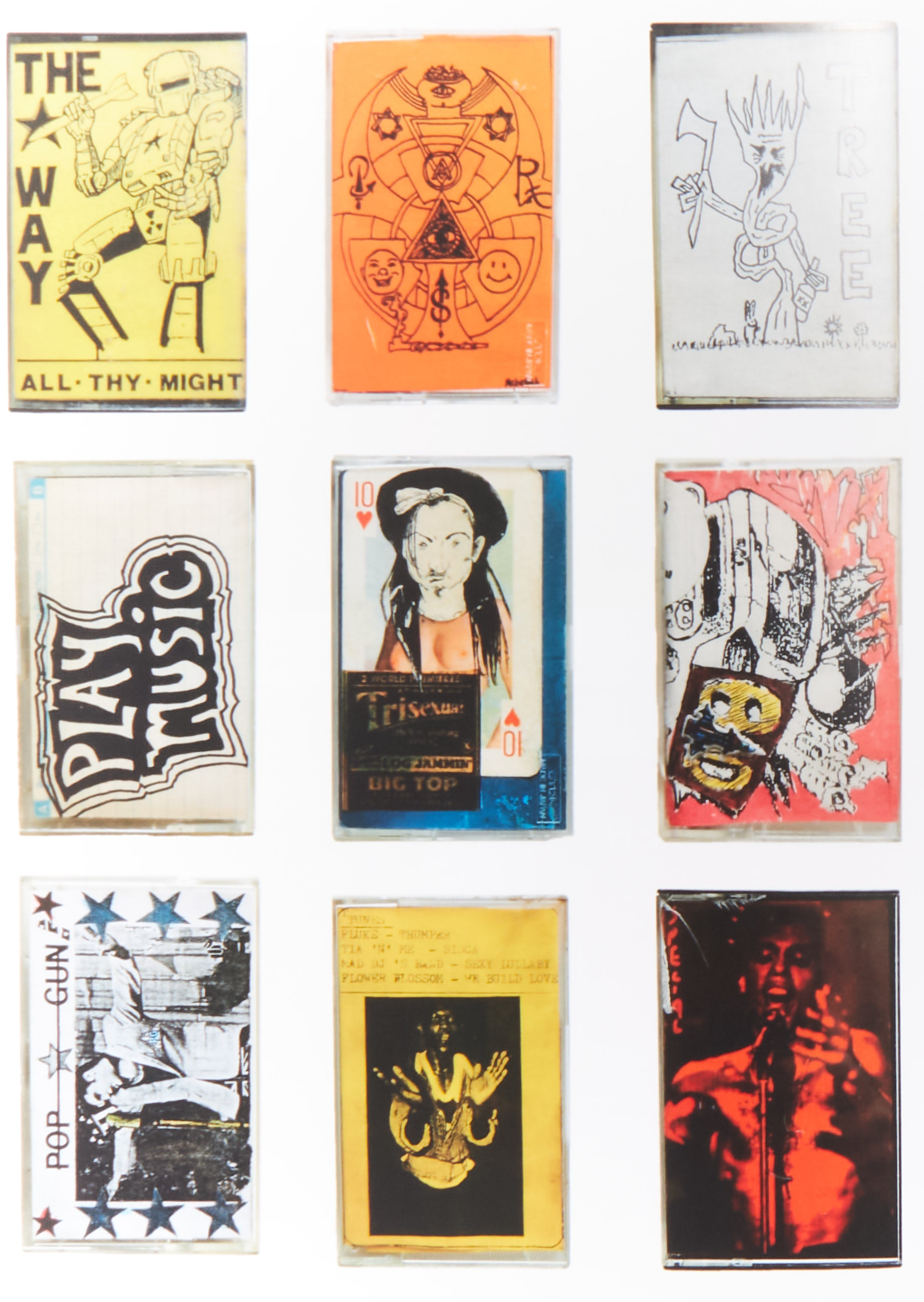

Image from RRPL Issue 1

Author

Holly Connolly

Published

July 08, 2025

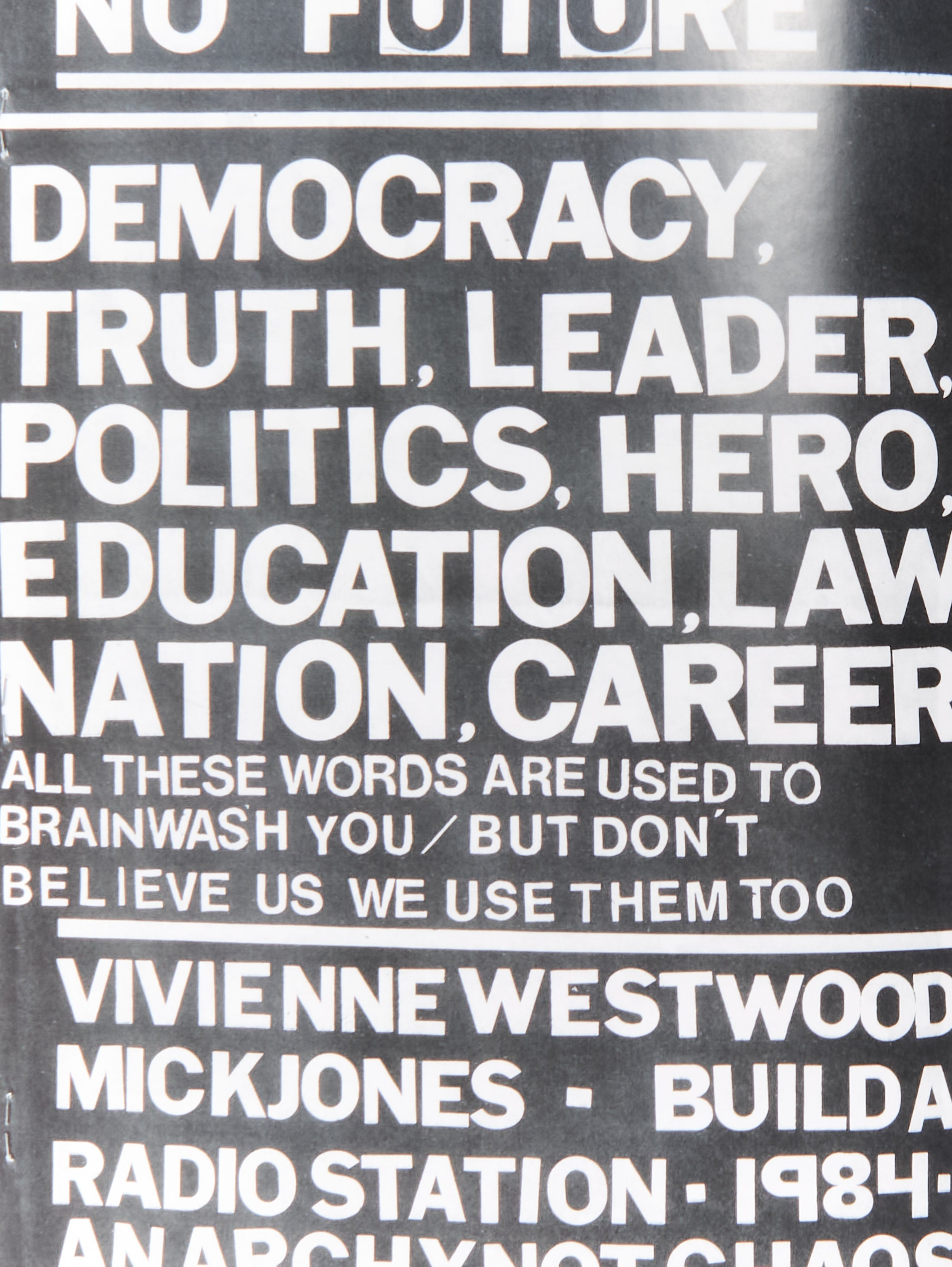

The musician and producer Mick Jones’ career stretches back through the late 1970s, a period in which a string of experimenting with early punk bands led him to co-found The Clash. Through the 1980s he founded General Public and Big Audio Dynamite, more recently he has been involved with the Gorillaz, and he has worked sporadically as a producer for decades, including with The Libertines. Parallel to playing his own part in shaping music history, he has also been creating an archive; a lifetime’s worth of ephemera that he has dubbed the Rock And Roll Public Library.

Following a run of exhibitions, now the Rock and Roll Public Library is launching a magazine, a means of making Jones’ huge catalogue of material available to everyone. In this endeavour Jones is joined by a team including Kirk Lake, a writer, musician and filmmaker who assists with archiving material, co-curating exhibitions and co-editing the magazine. “What’s particularly interesting, and what makes it unique, is that the RRPL is one person’s collection; everything in it has been selected and collected by Mick. It’s his view of the culture that was happening around him, that inspired him to create the music that he made,” says Lake.

“In a recent exhibition we had in London, we had one of Mick’s old mixing desks with coloured cables running to themed sections which loosely mirrored the magazine sections. So there were themes including ‘kids’, ‘teenage’, ‘fandom’, ‘DIY’. I guess that is the essence of what we are trying to do. Share these things that were Mick’s inspirations and hopefully inspire other people to go out and make new things.”

Here Lake discusses sorting through the collection, the importance of the physical, and how they made an archive a magazine.

The RRPL Magazine was born out of an archive of material that Mick Jones began collecting decades ago. Can you tell me a little about it, and how you became involved?

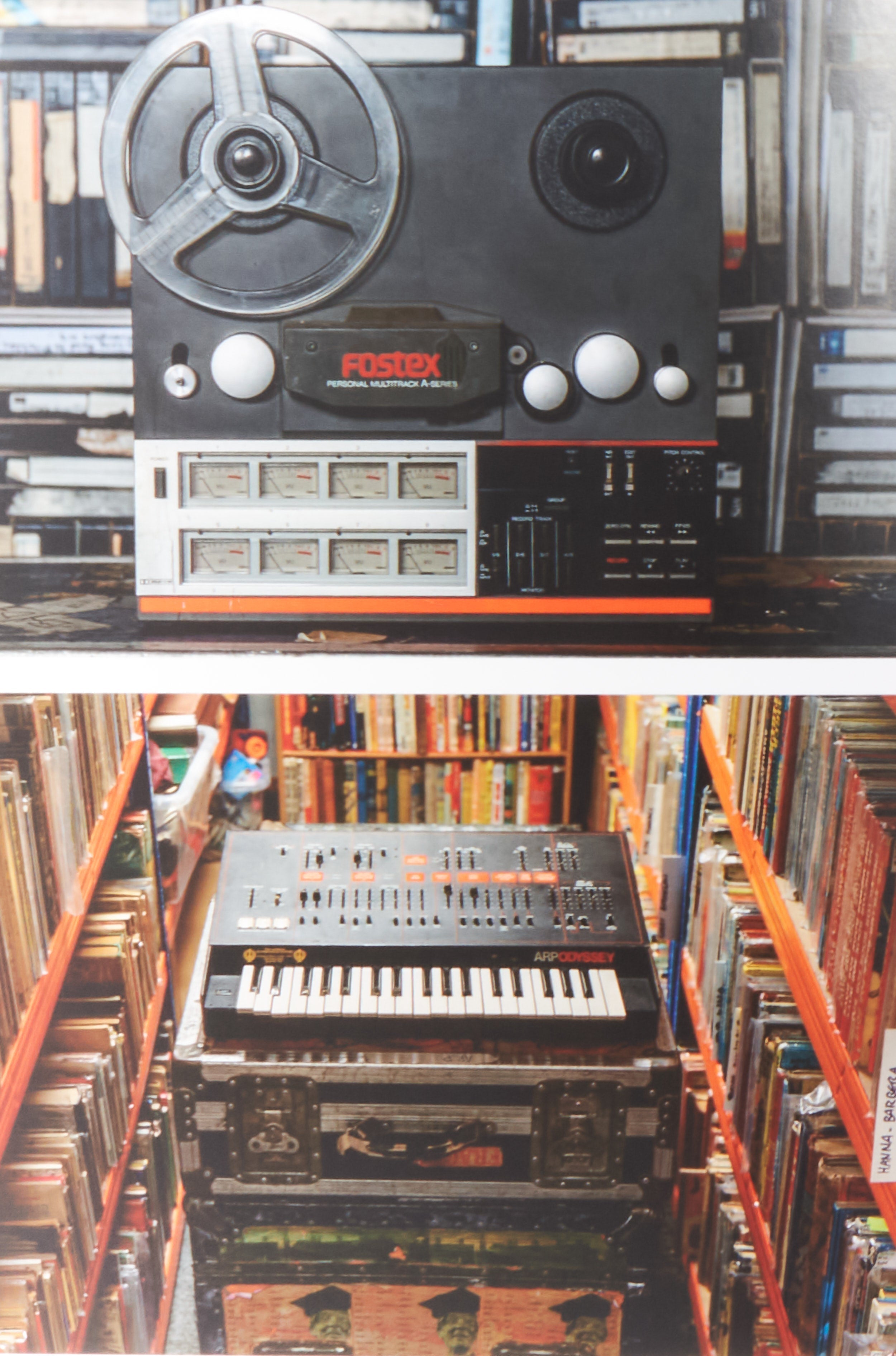

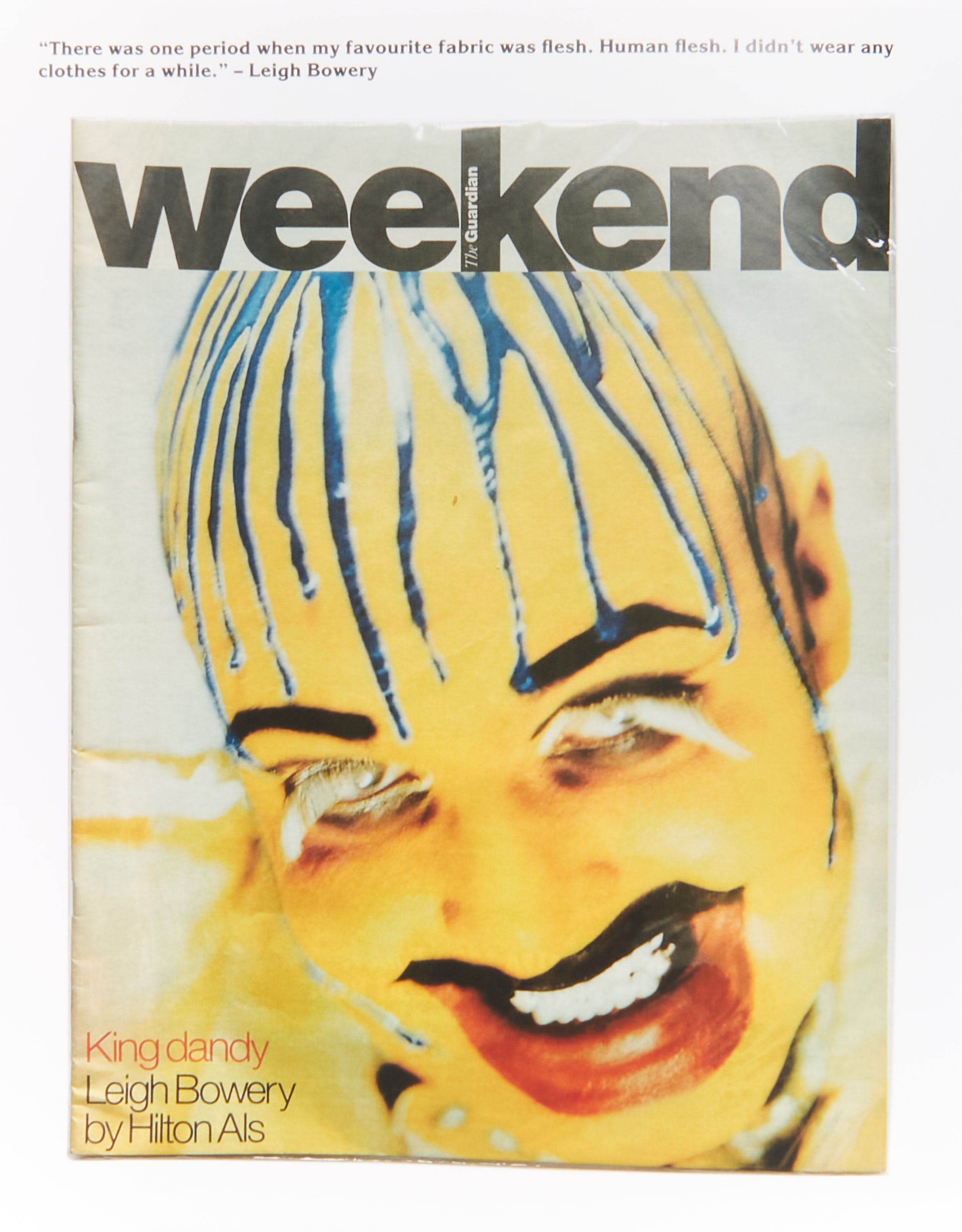

The Rock and Roll Public Library is the term Mick coined years ago for his vast collection of pop culture items and ephemera. We’re talking tens of thousands of objects ranging from books, magazines and comics, through to music and film in every format, posters, photographs, musical equipment, toys and games – the list goes on. Some of these date back to Mick’s childhood, other items are things accumulated over the years. Mick was fortunate to have been right at the centre of a huge cultural movement in the mid 1970s and onwards, and was in successful bands which toured the world. So the Rock and Roll Public Library is both an international collection, as well as one that reflects what was going on in Britain during those years.

I’d known Mick for more than 20 years when we began working together, and he’d always said that one day he was going to get me in to help sort out the collection. It started when he was having to move out of a small recording studio he had kept in West London, next door to which was the bulk of the collection; in a warehouse full of racks and boxes piled right up to the ceiling. This all had to be sorted out before the move.

What was your first interaction with the archive? How did it feel to go through all this material by hand?

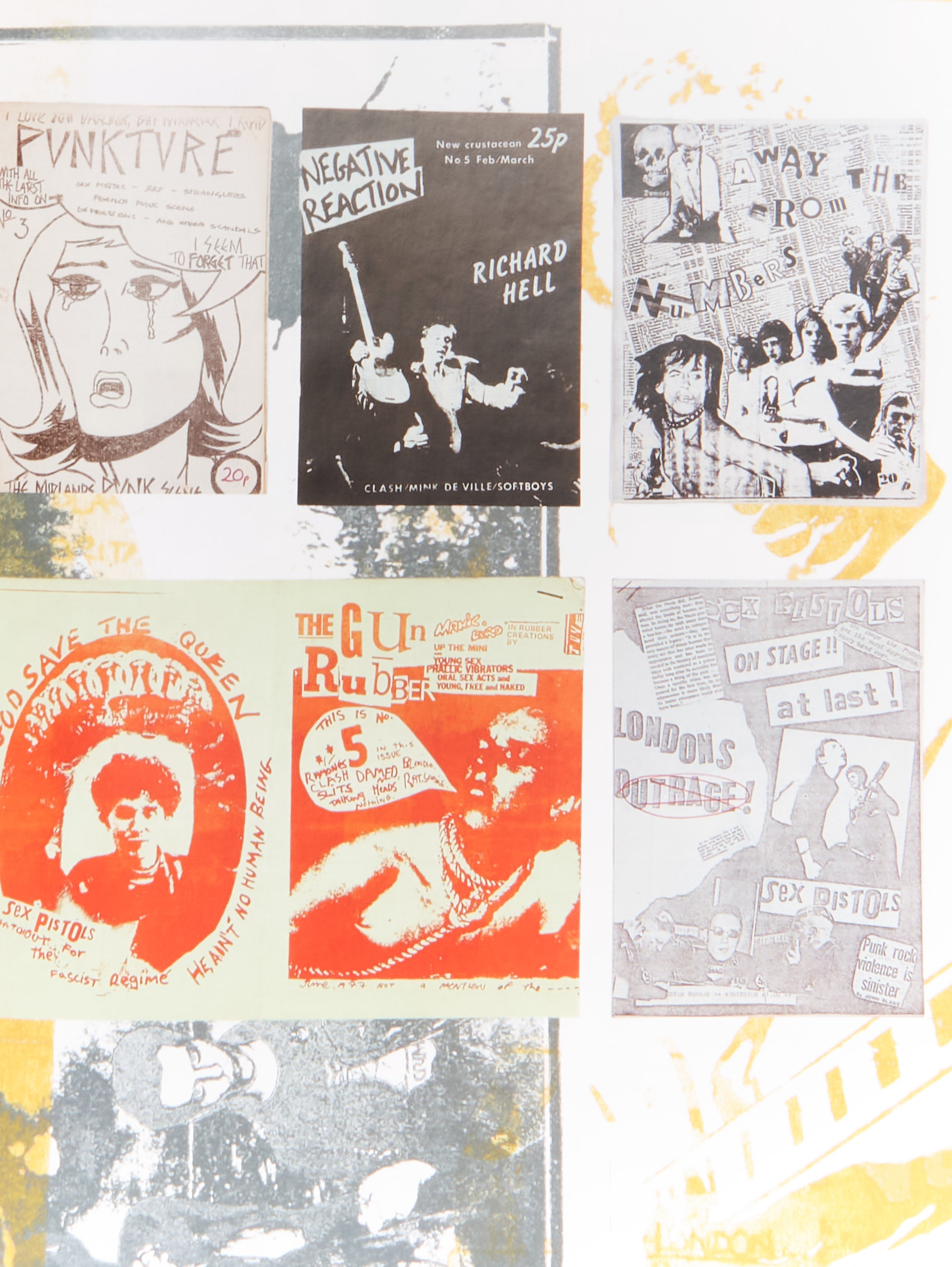

Although there had been exhibitions of the material stored in the Rock and Roll Public Library before I was involved, these shows had always taken more of a maximalist approach; filling a space with a quantity of objects. The reason for this is that the collection had been stored in no particular order, meaning that it was difficult to take stock of all the pieces in the collection. Mick has typically great recall, so he’ll usually know whether he has something or not. However, at that time, knowing precisely where that something might be was very difficult. And even with Mick’s great recall, when we were digging through boxes we still might find things that Mick had forgotten about, often related to his career. I remember notebooks with lyrics from his days with The Clash and very early posters and flyers from the punk era. Or even very recently we discovered an acetate for “This Is Radio Clash” with a cover custom made by Futura 2000 that Mick hadn’t seen since the time it had been made.

Image from RRPL Issue 1

All collections have an element of autobiography to them

For years now the team have been running exhibitions of this archive material, why was it time to begin a magazine too?

It took us about three years to sort out the collection and get the items into sections. Only after that process was it possible, for the first time, to have an overview of everything that was in the collection. We had the idea of being able to do a different kind of RRPL exhibition which would be more streamlined, and we thought a magazine could be a portable exhibition. It was about having a means to share some of the material, and I think Mick had always wanted to edit his own magazine too. Although instead of the title ‘editor’, he likes to say he is the magazine ‘producer’. He feels he produces the magazine the way that a record is made; changing things, tweaking things here and there.

Image from RRPL Issue 1

With such a vast archive of material to draw on, how did you decide what to include in the first issue? What felt vital, and how did you narrow it down?

The first issue acts as a general introduction to the collection. It’s broad in scope in that we have items that represent the breadth of what is in the RRPL. Then, as we move forward the issues will become more focused, like the second issue, which will be focused mainly on London.

In order to give the first issue some narrative cohesion, we arranged the material we wanted to use in a very loose chronology: you follow an imagined individual through childhood, into being a fan, then into making their own art (be that music/zines/film), and then into getting on stage to perform, and then finally getting out to see the world.

All collections have an element of autobiography to them – what we collect says something about who we are. So, although it was not what we set out to do, certain autobiographical elements from Mick’s life appear in the magazine. Some of these are obvious, like his drawings from art school or the poster he made for his very first band.

Image from RRPL Issue 1

It’s incredibly important to embrace the physical

Relatedly, both the exhibitions you run and the magazine too are physical ways to present the archive material. Why do you feel this is important, as opposed to say digitising the material and letting it live online?

Especially in our current moment, I think it’s incredibly important to embrace the physical. Take a copy of a magazine from the 1920s; it’s both a fragile object but also an incredibly resilient one. The words and images on the page are still completely accessible, and they could remain accessible for another couple of centuries or more. The value lies beyond the editorial content too – the small ads, the letters page, the snippets of news – there is so much incredible context of the era available by just turning the pages. Whereas, speaking digitally, we have computer disks in the RRPL that can no longer be read, and these are maybe just a few decades old. Or we have Digital Audio Tapes that can only be played when our unreliable DAT player decides it wants to work. This is fascinating, and so relevant to archiving too – there’s a whole section in the magazine addressing dead technology.

I think, also, that one of the elements of our last exhibition that people enjoyed so much was the fact that we included a lot of objects that could be touched and interacted with – books and magazines to read, records and VHS tapes to play.

We made a decision not to do a digital version of the magazine because we wanted to celebrate the physical. We’re not completely against technology. We do run a fairly active instagram account on which we share items from the archive, and we’ll be digitising a few pieces to run on our website in the future. However, I think the idea of the chance encounter, and the strange juxtapositions you get from browsing through and interacting with real objects, is difficult to replicate with a digitised, ordered, and categorised archive.

Image from RRPL Issue 1

The aesthetic of the magazine feels like it too could be from a past era. How did the design come about?

We knew we wanted to include full page, period adverts within the magazine, in the same way they had been used in their original contexts. Then we added in a small adverts section that we culled from the back pages of various magazines and newspapers. As we moved forward, we had to create a layout that allowed the use of vintage material in a more natural way, so that it didn’t look like we were just butterfly pinning old things and saying, “Look at this nostalgia.” The intention was to make the magazine look like it could have come from any period that wasn’t ‘now’.