A German Teacher by Amalia Ulman

Author

Holly Connolly

Published

September 17, 2025

In 2014, aged 25 and a recent graduate of Central St Martins, Amalia Ulman began a social media performance, Excellences and Perfections. Over the course of several months, Ulman narrativised a lifestyle through Instagram and Facebook posts, including ‘undergoing’ a plastic surgery makeover. Her final act, by which time she had nearly 90,000 followers, was to reveal it had all been a hoax. Dubbed ‘the first Instagram masterpiece’, the work caused a sensation in the art world and beyond it, and was a prescient consideration of feminism, performance art in new spaces, and the role social media might have in warping representations of reality.

This early career success, however, didn’t sit easily with Ulman, who felt ill at ease within the apparatus of the artworld and, as the years unfolded, frustratingly typecast by misreadings of her early work. She continued to produce art, but began considering how her preoccupations – in particular with narrative pieces – might fit within other mediums and realms. In 2021 Ulman released her debut film El Planeta, marking the beginning of a new career within the film industry.

“I was lucky that I received a very warm welcome for my first feature from a lot of people who had no idea about my previous work as an artist,” Ulman said, over the phone. “That felt very freeing and validating, that the work was standing on its own and being appreciated by film people who had no context of my previous work. It feels very good to make something that lives on its own, instead of because of the clout of the previous work.”

Since then, she has gone on to direct 2025’s Magic Farm, and is now adapting her short story, The German Teacher, into a new film too. Here she discusses the limitations of the art world, her interest in desperation, and finding the right audience for her work.

I trusted my galleries too much

One big thread running through your work, from your earliest pieces, has been a narrative arc. For me this is the thing that connects your projects across different mediums. Why do you think you’re so drawn to making narrative work?

The narrative arc is not something that I intentionally chose, and I think that’s what originally brought me a lot of trouble in fine art, because it's a medium that’s not really meant for a narrative arc. The work I was making usually required an audience to have some sort of attention from beginning to end, and the problem I encountered was that a lot of it would be taken out of context. For instance photographs of me would be read as merely, and I don’t say ‘merely’ as a bad thing, but merely a photographic piece, when it was actually part of a larger structure. It was about fabricating a fictional story with a fictional character and the photography was not meant to be on its own, floating in limbo, but instead was meant to be read in conjunction with the story part.

Obviously some people got it, especially younger people, but many older people didn't, but still sort of monetised the work, and tried to frame it in whatever way was convenient for them. I think at the time I trusted my galleries too much, but obviously they were driven by profit, and I think that damaged the way the work was understood. That made me kind of depressed, and I felt a bit trapped. I felt like I was only getting success for a work that was being misunderstood. I'm aware that sex sells and the image of a young girl sells, but it was distracting from everything else that work meant. Transitioning to filmmaking was not only a natural thing to do, but also very liberating, because for the first time ever I was not considered a hoaxer. Instead, I was considered an artist and storyteller. Finally, I felt understood, supported and respected for my work the way I wanted to be.

I read in another interview that you quit all your galleries last year, though you haven’t quit art. What do you think about the relationship between actually practicing as an artist, and the art world and apparatus around that?

I never felt comfortable in the art world, but mostly because of my personality type. I'm not good at partying, and I think that to make it as an artist in the fine art world, you have to be really good at partying. Another thing that I'm bad at is hanging out with really rich people, especially when I was younger. I was in such desperate need of everything – food, shelter, everything – that it was very hard for me to keep a straight face when dealing with millionaires.

That is obviously also my fault, because I didn't have the knowledge or know anybody who could guide me in terms of what it means to be represented by a gallery, and all the commercial aspects of art. I was very naive. I was just making art with the very limited resources that I had, but I didn't have anyone to guide me and to help me avoid making decisions that were premature or wrong.

Finally I'm in a position where I really enjoy my life as a filmmaker, and I would love to continue to make art too, but just for its own sake, not for some gallery exhibit. If I ever want to work with anyone, it has to be somebody who understands the work, not somebody who just wants to sell prints and stuff.

A German Teacher by Amalia Ulman

The things you experience will inform the work

Do you think it makes sense, as a creative person who produces narrative pieces, for your work to exist in the worlds of film and literature, where it's expected that there is some arc like this?

Yes, because the work doesn't get questioned. What I was also upset about, in a fine art context, is that instead of fiction, the work was called a hoax. I'm a ‘con artist’ instead of a playwright. I would get asked really stupid questions, questions that you would never ask an actor, things like, ‘How can you have a normal life after performing this role?’ It’s like, ‘I don’t know, how any other actor would? It's not that crazy.’

Recently, I was speaking with a male friend who's a writer, who does workshops, and he was so frustrated that every female writer he works with, they always get questions like: Is this autofiction? How much of this is real? No matter how much you repeat that it’s fiction, it’s like, ‘No, that can’t possibly be true.’

The book is dedicated to Raquel, and there's also a character in the book called Raquel. My impulse wasn’t to assume that meant it was a true story, but that you were being a bit playful with that relationship between reality and fiction through the dedication.

Raquel is a friend from high school, although neither of us ever had an affair with a teacher, nothing else featured happened. Recently I was asked about Magic Farm, and, yes, my grandma has a role, but none of it is autobiographical. I would say the same of El Planeta; the only thing that is true is that my mother and I lost our home, and I used the knowledge of how that feels to inform the film. But other than that, everything is fabricated or inspired by these other two women from my city. I think there's this lens that is put on the work of women particularly, which is funny, because I feel like all male directors also take from their own lives. It’s just a given that the things you experience will inform the work.

It almost feels like it's asking the wrong question: “Is this true?” Rather than, “What value is there in the work?”

Yeah, as long as the work is good, I don't think it being more or less autobiographical is relevant.

I know you're currently making a film based on this book. What is the relationship between the film and the book?

I always say in interviews that there's something that clicks when I'm about to make a film, that I see the first scene of the film visually, and then everything comes after that. That’s how it happened with both El Planeta and Magic Farm. But I was thinking recently in terms of The German Teacher and I realised, ‘Wait, it didn't really happen that way, because I did write the short story first.’

It was more like a general feeling with this project, starting from the short story, and the vision evolved a lot. Instead of moving in a linear way, it moved in many different directions; it expanded from every corner. I also kept it very, almost blurry, in my mind, because I didn't want to get attached to any specific actor. Now the film is crystal clear when I think about it. It’s funny though, I had to revisit the short story recently after working on the script for so long, and I thought, ‘Oh, this is crazy, because it's missing this character, this other character, this thing doesn’t happen…’

So they almost become separate projects in a way?

Totally. For instance the ending of the short story. It works really well as a short story, but when it was fleshed out in the script, it was so cringe. I think there's something more dream-like about a short story, or it's more like a poem. You don't have to see it that clearly, or map it out, it's more like a feeling that you get. Then when you try and flesh it out as a film, ‘Here are all these actors that we need, this is what they should be doing.’ It’s like, ‘Oh my God. It wasn’t supposed to be this specific.’ It's funny that, to bring to life the intention of the short story, it's not really just about translating it into a film, but more about adapting.

A German Teacher by Amalia Ulman

I’m interested in desperation

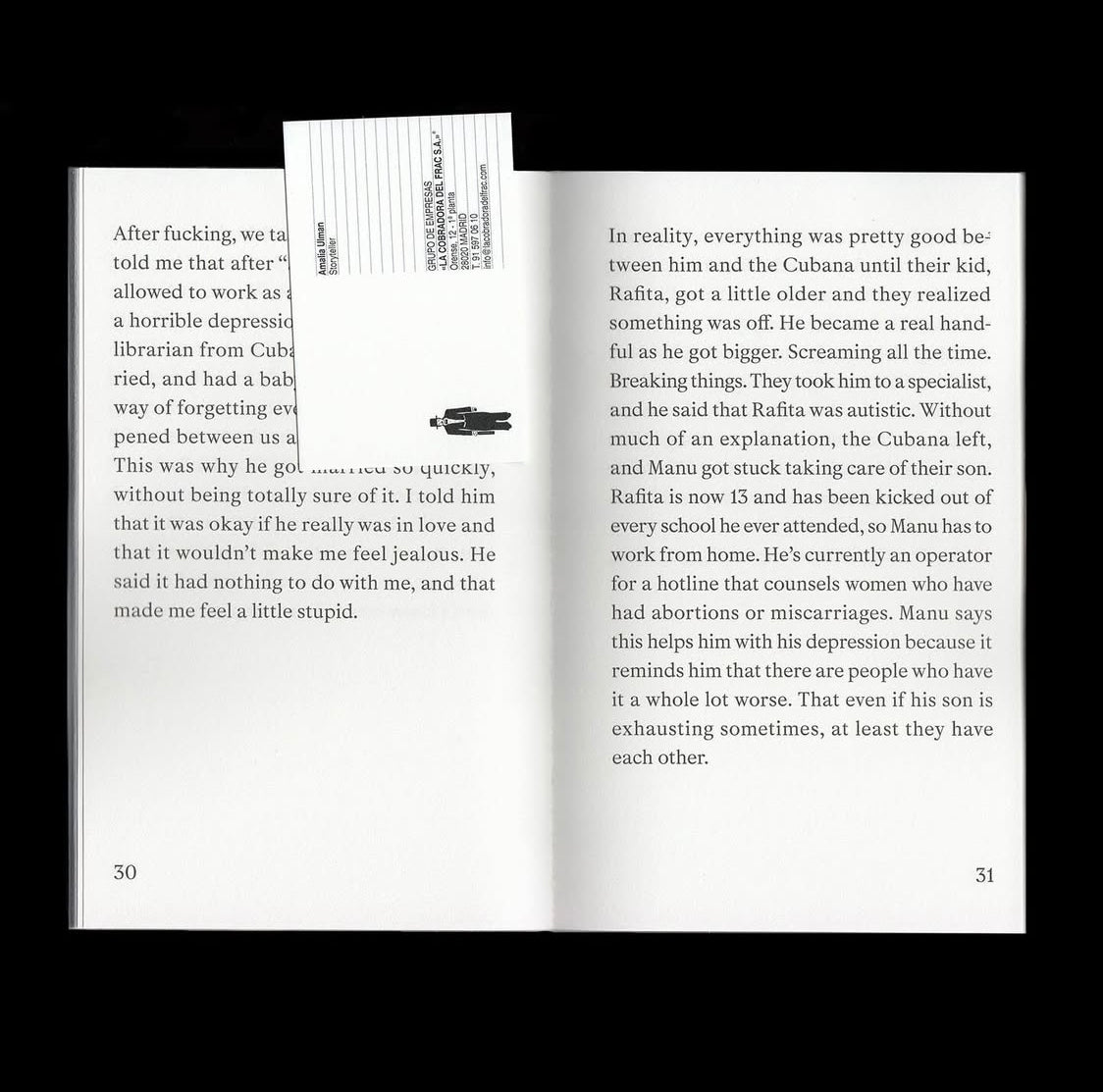

Financial precarity, work and office culture, are recurring topics in a lot of your work. In this book the protagonist has long been unemployed, and the job she does get is as a debt collector. Tell me about your interest in these subjects?

To me, it would be impossible to leave these things out, because precarity has always been part of my life. Also, I’m interested in desperation, and doing crazy things out of desperation, things that might never have happened if you had a stable income or security. There are certain circumstances that make for good films precisely because they mean characters have to step outside of the ordinary. It’s like, ‘Okay, this seems like a bad idea. But not doing this is worse.’ I think those kinds of conditions put characters in situations that make for good stories.

The book is in part a depiction of trauma, and you explore aspects like a victim trying to claim agency in the aftermath of abuse, as well as patterns of repeating behaviour. Tell me about how you approached writing about trauma?

The girl in the book never really managed to settle in life properly, or thrive, because of this trauma. Part of trauma is that you unknowingly behave in certain ways because of it, and only years later you can say, “Holy shit, I was stuck for years because I never got to see this through.” It happens with a lot of instances of sexual abuse; it can be very hard for victims to move on. It's like they get stuck in a limbo, and I think I wanted this character to go through that.

I was saddened to hear that some people felt The German Teacher was cynical, or an instance of me being a provocateur. Really the story is completely against sexual abuse, and is about the dangers of pretending that it doesn't have any side effects, and the dangers of claiming that a teenager can have any agency.

My work has always been very earnest

I wonder if, unfortunately, the earlier reception you had in your career has come to haunt projects like this a little bit?

It always comes back to haunt me, in a way that’s very frustrating because my work has always been very earnest. Even when working with fiction, even in terms of the projects where I was lying to people, that was only ever for a period of a few months. Then part of the project was that I would immediately come out and talk about it as a work of fiction, nobody lost any money or anything, the only disappointment for a lot of people was that I hadn't gotten a real book job. I like for my work to be layered. And of course, if you don't look at everything underneath each layer, it can seem superficial.

Seeing the book be misunderstood provides a good exercise for making the film though, to depict it in such a way there’s no way around the meaning. I’m intending for the film to be more like a love story between her and her friend.

Given that your work has sometimes been taken out of context, do you find it hard to create work and then release it into the world, knowing that you can't really control how an audience member receives it?

Not really, not in film. El Planeta was so well-received, and people totally understood it. It was so cool to receive, I mean sad too, but it was cool to receive a lot of emails from people who grew up in their mother’s car, saying, “I love this film. Finally, I see some realistic representation of how this feels.”

With Magic Farm, it premiered at Sundance, which is mostly industry people, and all these industry people in America, at least, are white and middle class, it’s very homogeneous. There, the film wasn’t that well-received. Then in Berlin, the reception was amazing, but when it got to the screening for Latinos, that's when it all changed, because it was very well received by Latin Americans. A lot of people finally saw their countries represented in a way that was realistic. Sometimes it takes longer, but when a work does finally reach the right audience, it’s very beautiful.

A German Teacher by Amalia Ulman