Photography by Mervyn Smith

Author

Holly Connolly

Published

June 24, 2025

Joel Seawright and Lucy Jackson first met when they moved to London, for a course for creatives entering the industry without university degrees. Seawright, who is from Bangor, in the North of Ireland, had a graphic design background, and Jackson, who is from Kent, in England, had a fine art and painting background. They began a relationship and creative partnership that would see them, after a seven year stint in London, relocate to Belfast, where they launched Rotten Magazine, and Rotten Books, an independent studio and publisher.

“We’d been thinking about it for a while, talking about eventually bringing our practice back to Belfast and doing something that felt meaningful there,” says Seawright. “For us, London was becoming increasingly expensive, and when our landlord decided to raise the rent, we were forced to start thinking about options. Still, we hadn’t seriously planned on uprooting our lives just yet. Then my dad was diagnosed with cancer, and that was really the moment everything shifted.”

Continuing in the spirit of Rotten, they’ve now published Fantasy Island, a beautifully nuanced consideration of the last 50 years of Irish photography, told through the work of 70 Irish photographers. Sidestepping easy cliches around the complex history of Ireland, Fantasy Island instead explores the rich visual lexicon, nostalgia and mythology of the island. Here Seawright and Jackson discuss working together, the benefits of an outsider and insider perspective, and the meaning of fantasy.

It evokes an imagined place shaped by memory and longing

I’m really interested in the name Fantasy Island, for me it captures something of both the specific mythology of Ireland and the nostalgia of its diaspora too. How did you arrive at it?

Lucy Jackson: The name Fantasy Island actually comes from the Elliot Smith song “Strung Out Again”. Choosing the name was a bit of a challenge. We wanted something that could speak to both the North and South of Ireland without alienating anyone or falling into cliché. Fantasy Island felt like the right fit because it evokes an imagined place shaped by memory and longing. It leaves room for interpretation, which is essential.

Photography By Donovan Wylie.

We’ve learned to lean into our individual strengths

Your creative partnership began when you founded the magazine Rotten. Why did you decide to evolve into making a book? And how would you describe your way of collaborating?

LJ: We decided to take a break from Rotten because it felt like we’d said everything we wanted to say with the magazine at the moment. We were ready to try something new and challenge ourselves in a different format, and the book felt like the right next step.

In terms of collaboration, our working styles are pretty different, and in the beginning that definitely led to some friction. But over time, we’ve figured out what works: we tend to do our best work independently, then come together to shape things at the end. We’ve learned to lean into our individual strengths and delegate based on who is best suited to each part of the process.

How do you find working together as a couple specifically, has this dynamic always been a part of your relationship?

LJ: Working together has definitely become a big part of our relationship. Early on, we were each doing our own thing, following separate paths and projects. But over time, we naturally started collaborating more. We’ve got quite different strengths, which actually works in our favour and helps keep things balanced. There are occasional challenges – like making sure work stress doesn’t spill into every conversation – but overall, it’s really rewarding to work as a creative duo. It’s great to build something together that we both care about.

Photography By Matt Glover

What really anchors the book is its authenticity

Ireland has a long history of Hollywood and media portrayals, and even recently these can often ring quite false or overdone. I find this book beautiful for how much it resists these kinds of easy portrayals. How did you approach curating a project that captures the nuances of Ireland, and the kind of work Irish people produce?

Joel Seawright: One of our main goals was to avoid the kind of flat or stereotypical portrayals that often appear in mainstream media. By including such a wide range of perspectives, we were able to reflect the complexity and contradictions that exist within Ireland.

What really anchors the book is its authenticity. The work comes from people who’ve grown up here and who understand the nuances in a way that can’t be imitated. We were careful to avoid images that felt overly staged or performative, and instead focused on work that felt honest and rooted in real experience.

Equally, Fantasy Island doesn’t shy away from depicting The Troubles, or other difficult parts of Ireland’s past. How did you strike the balance between what people might expect to see of Ireland, and what might surprise them?

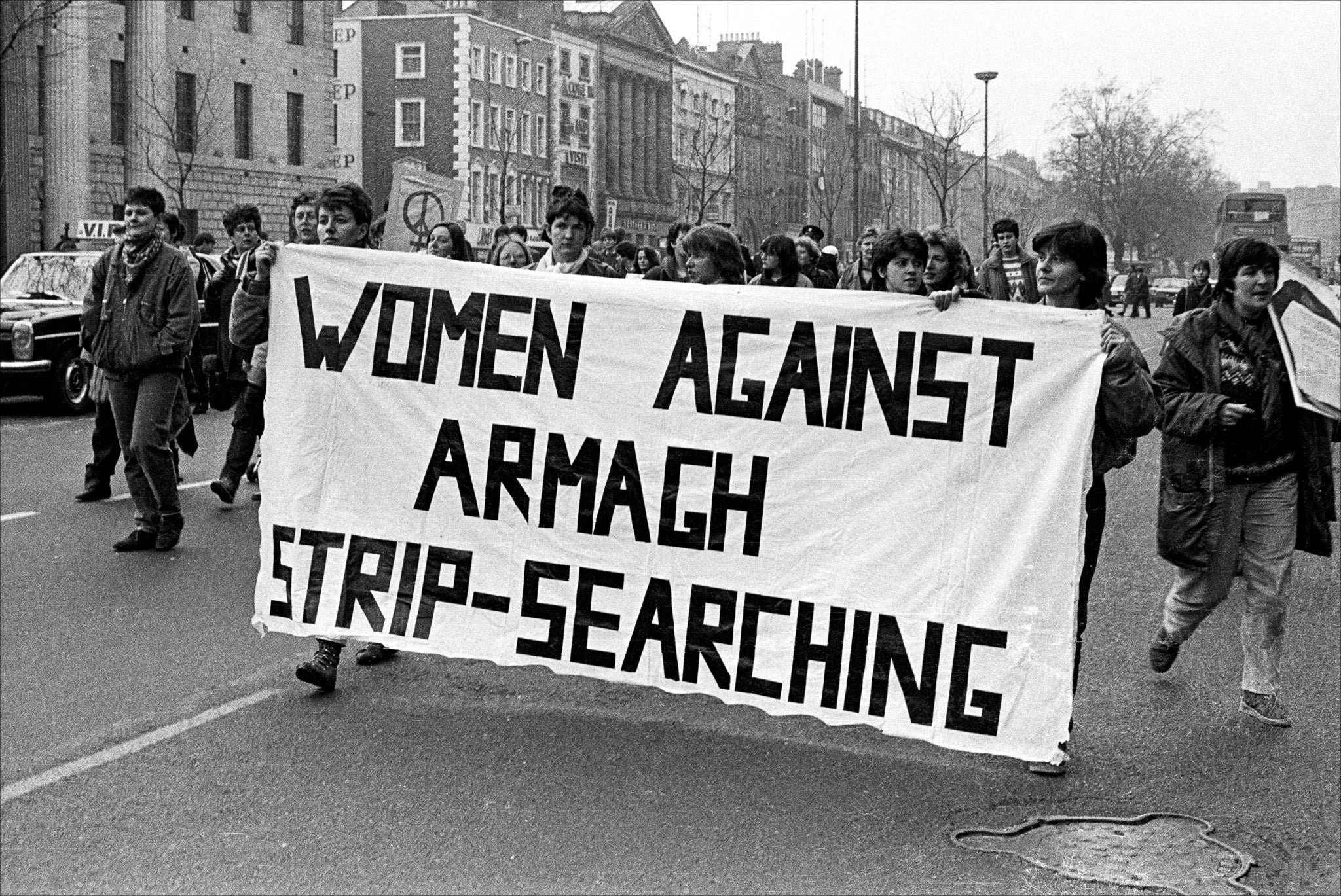

JS: We didn’t set out with the intention of focusing on the Troubles, in fact, at first we tried to steer clear of it entirely. It’s such a well-worn subject, and we were conscious of how often this has often been reduced to a narrow or predictable narrative.

There’s so much more to the history and people of Ireland that often gets overlooked. That said, because the book begins in 1975, it was almost impossible not to include it in some form. Rather than centering it, we aimed to let it sit alongside other narratives, treating it as one thread in a much broader, more layered picture of Ireland.

Photography By Rose Comiskey

Fantasy Island covers 50 years of Irish photography. How did you decide what to include?

LJ: Once we had our shortlist of photographers, the next step was choosing images that worked best within the format of the book and that we felt a real connection to. It wasn’t just about selecting strong photographs, it was also about how they resonated with each other. We had to make some tough decisions and say no to a lot of images we liked. Sometimes a photo was too detailed or simply didn’t sit right on the page and it wouldn’t have worked.

Do you think your slightly different identities – Joel being from Ireland originally, and Lucy not, but now living there as an adult – might have given you a useful wide perspective?

JS: It’s definitely something we’ve talked about a lot, especially since this is such an Irish-centric project. But having Lucy’s outside perspective was really important. She was able to look at the work more objectively, purely from a visual point of view. Where I might hesitate to put certain things together because of the context or cultural weight, her ability to step back and focus on the sequencing without that influence was invaluable.

Was there any work or photographer that you discovered while curating the book?

LJ: While curating the book, we definitely came across some amazing discoveries. For instance, Joel met Jordan Hearns, who runs Smut Press, at the Bound Art Book Fair in Manchester back in 2023. By that point, we had already finalised the list, but after seeing his work we both agreed it had to be part of Fantasy Island.

Through the open call, we discovered a number of great photographs that we wouldn’t have come across otherwise. Photographers like Colin Aherne, Karl Magee, and Zoe Hamill offered work that felt important and fitting for the book, and we were excited to include their perspectives.

Photography By Gareth McConnell

Our generation is actively reclaiming its identity

What was it about Jordan Hearns’ work that excited you so much?

LJ: There was something really immediate and honest about Jordan’s work that grabbed us. It felt raw but also really considered, like every image had weight but without a sense of trying too hard. There’s a sensitivity to how he sees people and places that just resonated with us.

It feels like an interesting time for Ireland currently, both culturally and politically, and there has been a broader interest and engagement that I think is reflected in the popularity of recent books and films set in Ireland. Why did now specifically feel like a good time to bring out this book?

JS: When we first met eight years ago in 2017, we discussed the relevance and need for a project like this to champion Irish artists in their own words, though we never imagined we’d actually be the ones to create it. Putting a pause on Rotten felt like the right moment to challenge ourselves with something new. Politically and socially, Ireland is at a major turning point, and our generation is actively reclaiming its identity and questioning the country’s future direction. It felt like the perfect time to reflect that shift in the book.

You are both based in Belfast, why was it important to you to feature all of Ireland?

JS: While we're both based in Belfast, it was crucial for us to feature all of Ireland in the book. Part of the concept of Fantasy Island, at least our personal idea of it, was to imagine a unified country, free from British rule. The idea behind the book is that everyone featured has their own ideal fantasy of what Ireland could or should be, and that's why it was so important to include a range of perspectives to shape this vision. It’s also important to acknowledge that, for many of us, this idea of unity feels like a fantasy – one that, in my lifetime, may not be realised.

Photography By Edna Bowe