Author

Holly Connoly

Published

October 22, 2025

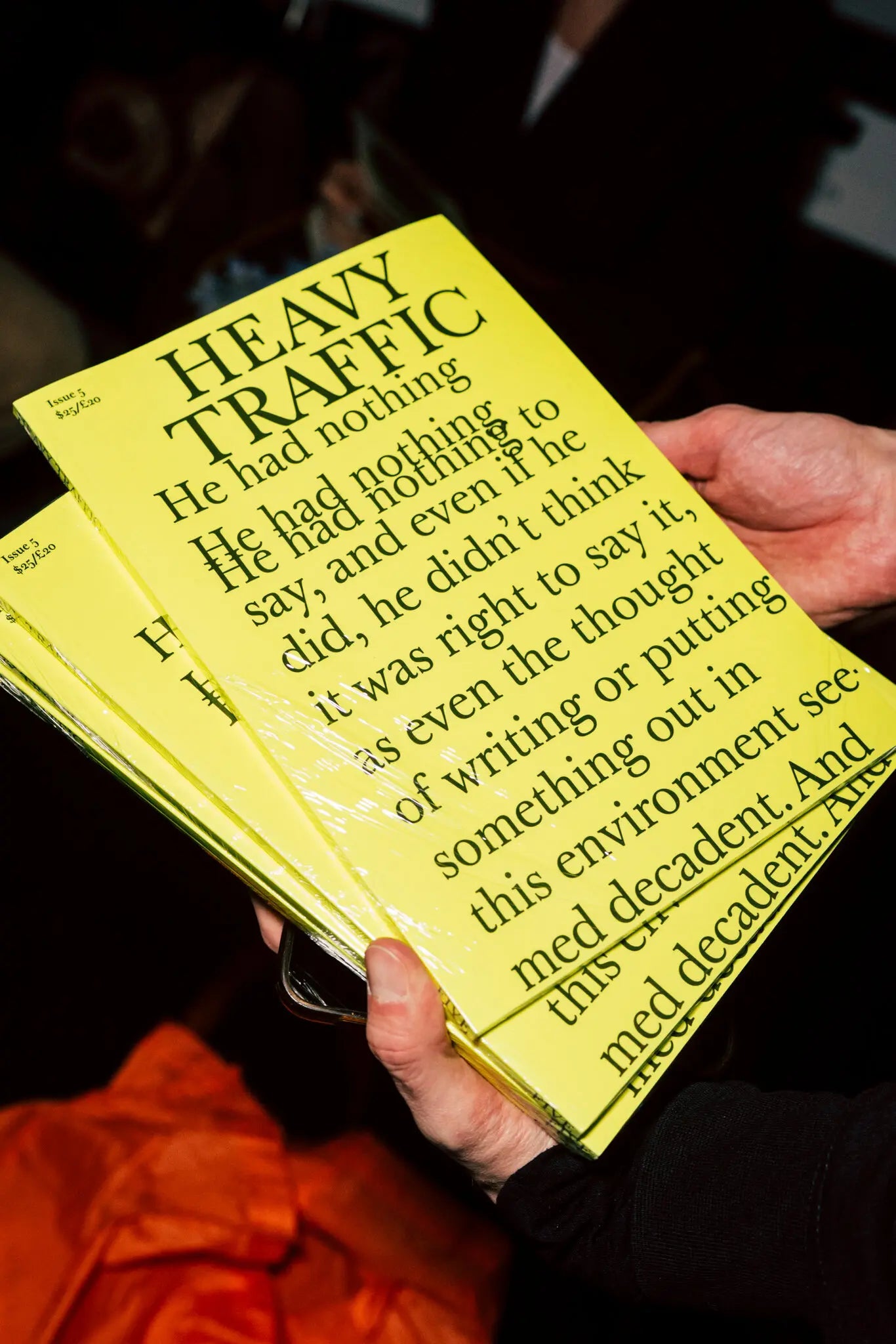

Heavy Traffic is disruptive. Now in its sixth issue, the magazine destabilises the aesthetic conventions of magazines – there are no images in its strictly black-and-white pages; the text functioning as something beyond just words on a page. “And how, at heart, it’s ridiculous to publish a magazine, and a fiction magazine at that, and how, it has to be covered with words, because the words are images, or become that way when you read them,” wrote editor Patrick McGraw in his letter for Issue Four.

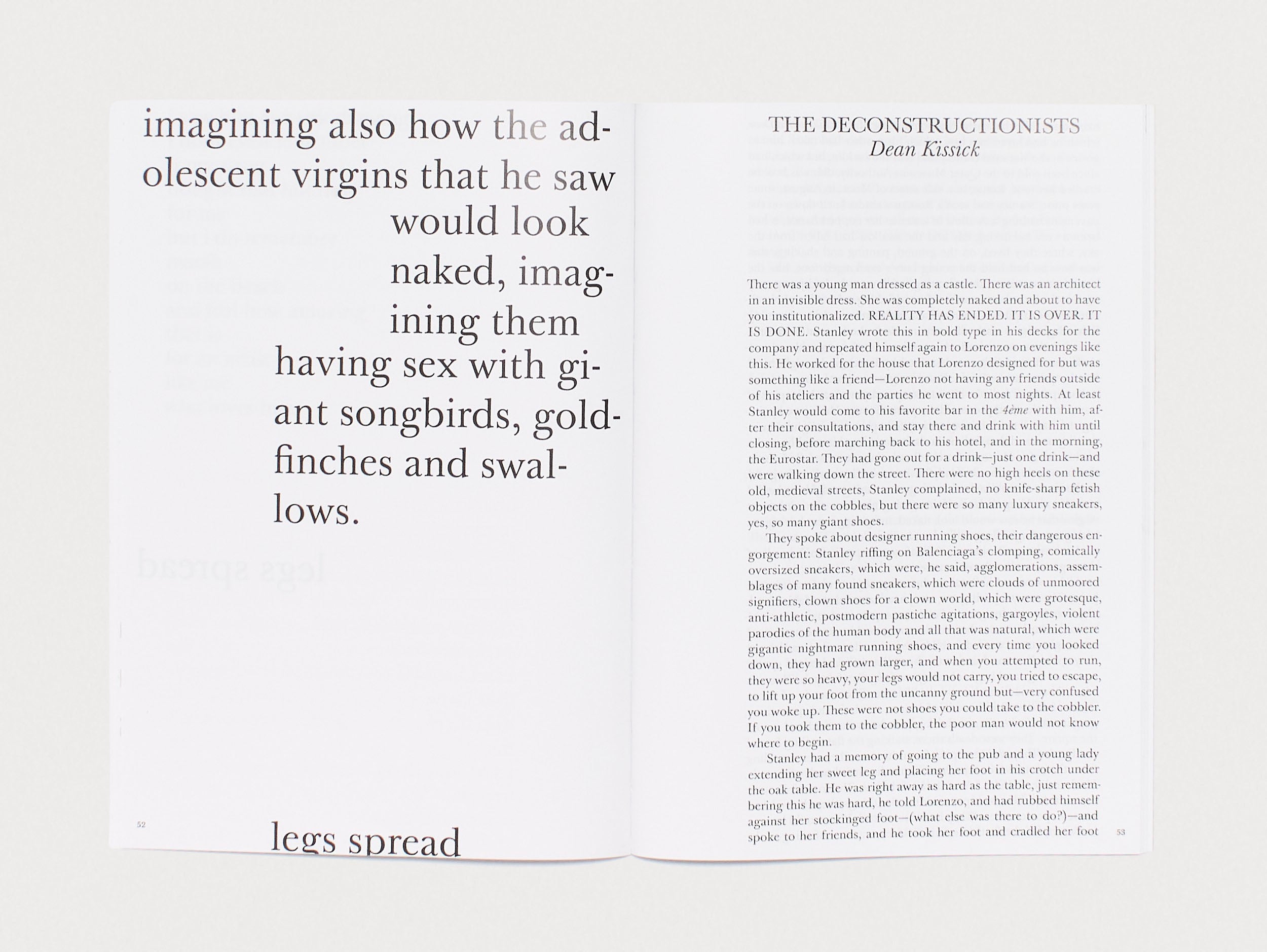

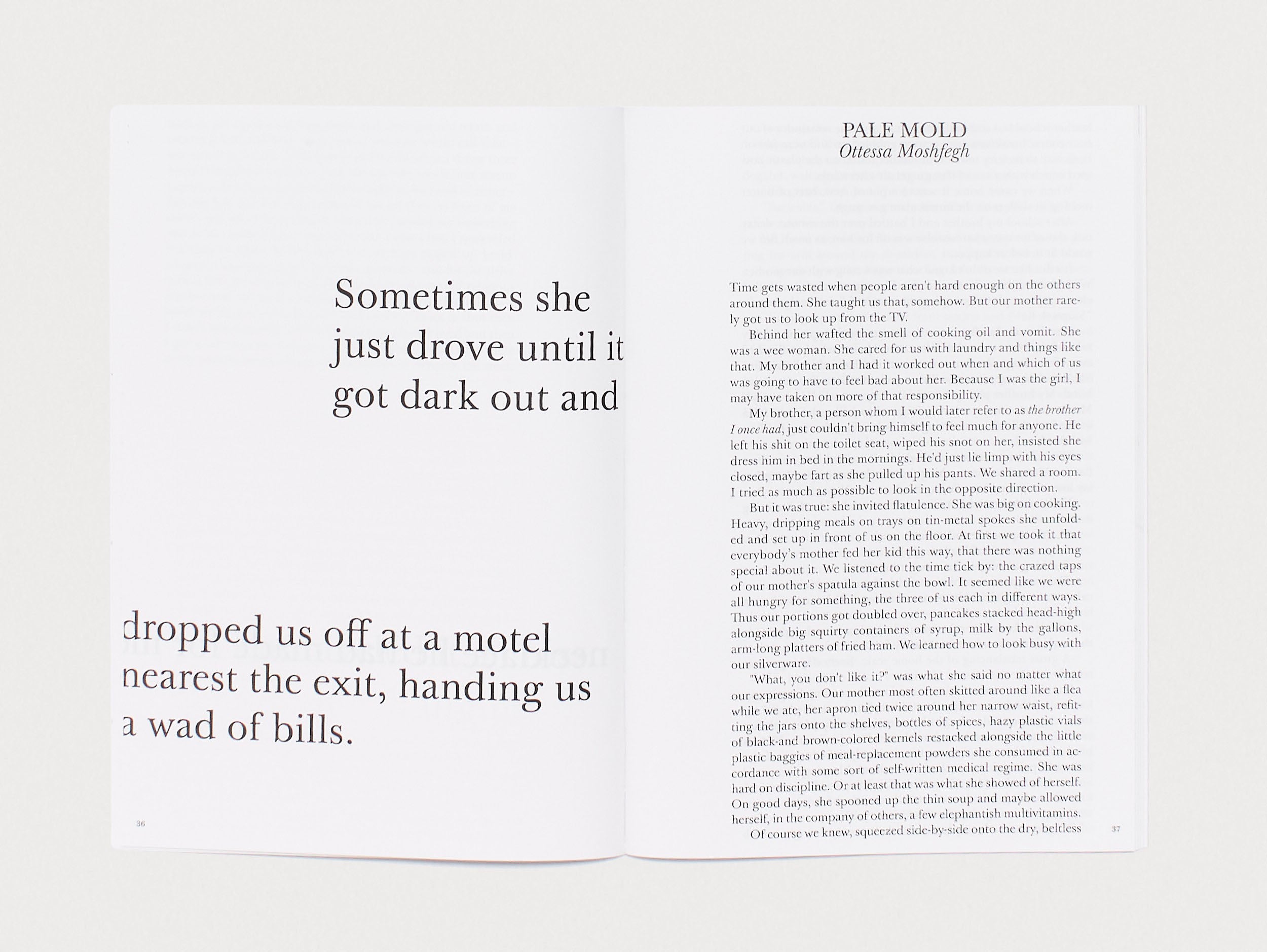

Then there is the writing itself. Informed by McGraw’s background studying architecture at London’s Architectural Association, Heavy Traffic runs writing that’s unexpected, by fine artists, architects, and writers alike. So far contributors have included Brad Phillips, Natasha Stagg, Sean Thor Conroe, Lynne Tillman, Mark Leckey and Amalia Ulman.

It’s a magazine that’s a perfect symbiosis of design, form and content. This is partly due to the vision of the influential designer Richard Turley, who came onboard after McGraw had designed the first issue himself. “The writing needed someone like Richard to bring it to what it is now,” says McGraw. “Within the first hour of our meeting it was apparent that he completely understood what the writing is, and I think that's what you see today.”

Here Patrick McGraw discusses contemporary architecture, the importance of voice in writing, and why he wanted to make a magazine.

You trained as an architect, balancing this with freelance journalism before moving into writing and editing full time. I want to start by asking about this route, and about how the constraints of one discipline and profession might have prompted this journey.

Architecture is a dying medium, in my opinion, if it’s not dead already. The school that I went to [the Architectural Association] certainly has a very brilliant history, and there are a lot of brilliant people there. But architecture today mostly just serves this kind of runaway, privatised real estate industry that's eating up the Western world.

I think there's this delusion that you can go into architecture and do whatever you want, be the next Richard Rodgers or something, but that’s very far from the truth. There are a lot of things to do with real estate, and other economic factors, that go into how you actually build a building. The short of that, is that you can't actually do what you want to do, really.

I still greatly love architecture, and in particular I love the way that architects see the world and the way that they research and write. I think it's one of the most rigorous mediums that there is. So I do really appreciate architects and architecture, but at the end of the day I think you have to be really quite delusional to be an architect in today's world.

Do you think the same could be said for writing and writers, albeit in a slightly different way?

Writing? I don't think that’s a delusion. I think it's more of a sociopathy or something along those lines. I mean writing is a very, very small market at this point, so I guess there is a delusion there as well. But I think most of the writers that I know, they're not delusional, because every writer I know is very aware of that fact.

That actually, in a way, can be very freeing. I'm excited at where writing is able to go now, because it is this very odd, increasingly niche subject. At the same time, language is incredibly important right now. People write more now than they ever have, in bizarre ways; texting and tweeting and all this stuff. So to be a professional writer is ridiculous to a degree, but writing is very, very important, and I think is the key to modern life, in a way.

But is there a danger that writing can become a little too insular? Because it is such a small market, and everyone who does it knows they are speaking to a small audience, does it run the risk of becoming too self-referential?

Yes of course, it can be very masturbatory and insular, in this weird way. For me, Heavy Traffic is a way of trying to get out of that. I do know a lot of industry writers and people in the industry, but I am definitely an outsider. Publishing writing by artists like Mark Leckey and Amalia Ullman, or by architects, is a way of breaking it open, or seeing things in a new light. By no means am I the first person to do that, but I could never justify it to myself if I was putting out a purely literary magazine, that was just publishing people from the very small literature world. What's fun about Heavy Traffic is it is a space where you can play with writing, and even expand that field.The smallness of the market for writing, I think, is something to be played with.

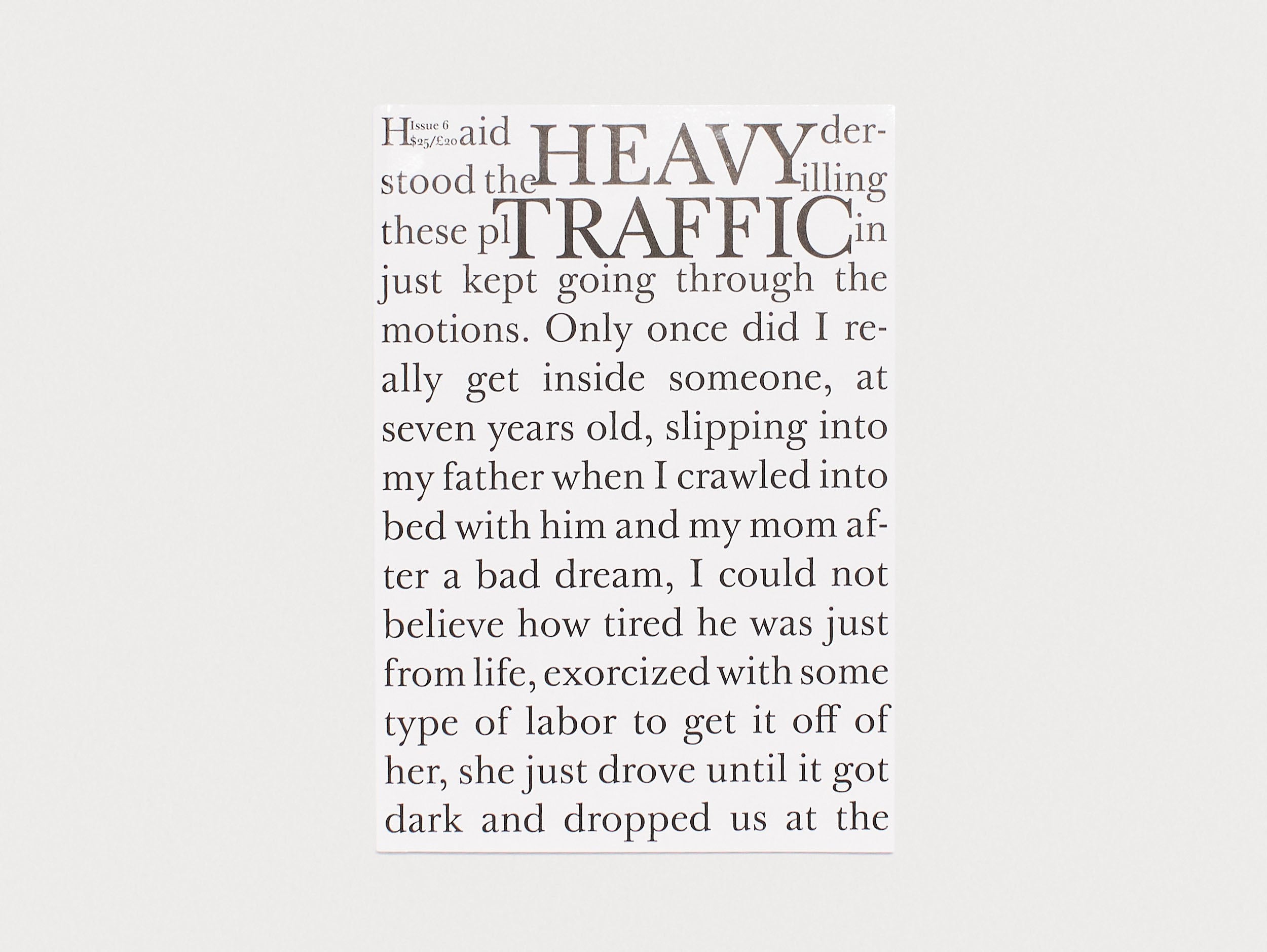

Heavy Traffic, Issue 6.

Language is incredibly important right now

Aside from the writing that Heavy Traffic publishes, the layout, and the way in which the text of the magazine arguably also serves as imagery, is one of the most notable things about it. How did this come about?

Well, I think the first thing is that a lot of people don't read; even if they buy a magazine, they might not actually read it. But with Heavy Traffic, every part of the magazine – the cover, the back cover, the inside cover, the flap – every single page is covered in text. So even if you only glance at the magazine, there's no way that you can't read it.

There's a long tradition in magazine-making of creating entry points for readers. Normally that would be an image, or a headline that was a different font type, and this would then lead a reader’s eye; they would start reading, and quickly get engrossed in the rest. I don't really think that happens anymore, but I do think that Heavy Traffic is a play on that concept. You open it up and there are so many font sizes, different types of pull quotes, all these distinct types of texts going on simultaneously, so it's impossible not to read something. Even just looking at the magazine is a form of reading it.

Then also, I believe that Heavy Traffic’s design opens up multiple ways of reading the texts. If you have a piece and the first three paragraphs are in 12 point font, and then the next one is in 20 point font, there are lots of ways to read it – you can read that fourth paragraph as an entirely different piece, right? So you can create this field of depth in the magazine, despite having no images whatsoever. It’s a field of depth in terms of meaning.

In terms of the lack of images, honestly, I think one of the main factors also was just that I am not good with images. I worked in magazines for years before I started Heavy Traffic, and I just never had a knack for images.

Heavy Traffic, Issue 6.

Heavy Traffic’s design opens up multiple ways of reading the texts

I read that you designed the first issue of Heavy Traffic yourself, before Richard Turley came on board. How did it evolve visually once Turley got involved?

I think if you're going to start something then you have to just do it. There's no point in sitting around and trying to get things perfect before you put the first issue out. So I decided to design it myself, very quickly, and base it off this old English literary magazine called Encounter. Then when I met Richard a few months later, within the first hour of our meeting he had already come up with what you see today as the main tenets of Heavy Traffic design – the pull quote right on the cover, no images, and it just being very quick and fast. The design leads you through the magazine very quickly, which gives it a quickness of pace.

What draws you to a piece of writing? What makes you want to publish something?

One, it’s hard to describe, and two, it has changed over time – it's definitely not the same thing that it was two years ago. I actually haven't really read the first issue, or some of the stuff that we put online, in a long time, and I imagine that if I read some of those pieces today that I wouldn't like them. So it has evolved over time, but I think if you look at any piece in Heavy Traffic, whether you like it or not, there’s a certain amount of character in it. I would even say there’s something related to a writer being able to write convincingly in whatever character that they're trying to portray; it has to be convincing.

I didn't grow up as a person who fetishised print

I asked a friend who works in publishing how he chooses what books he wants to work on, and he said something similar; that it’s to do with a writer’s ‘voice’.

It is voice. And voice is just one of those things that you either have or you don't. You can pretty much tell, usually in the first couple sentences, whether someone has it; it's just something that's embedded in the writing or it's not.

Do you think print media is having a resurgence? And could you run Heavy Traffic digitally? Would you want to?

I don't believe that the digital world is a very interesting place at the moment. I just can't imagine being excited about releasing something on Substack or on a website. I think the fact that the Internet is this over-policed platform world has made people want to come back into the analog world to a certain degree. Equally, there is no pure analog anymore. No one would know what Heavy Traffic is without the digital world, and like any other print magazine we only survived because of the digital world. So it's definitely not a purely analog thing.

I will also say, though, that I think it's slightly ridiculous to publish a print magazine when you get into the logistics and economics of it. The greatest contribution that any one of these new magazines could make, is if we could try to change the way that magazines are printed, and make it more economically feasible to print a high quality magazine.

I didn't grow up as a person who fetishised print. I grew up online, I read everything online, and it never really meant that much to me to be published in magazines. So I've had to learn all of it. And it is a shock, what a horrible business model it is. So I would like to develop a world in which it becomes economically feasible.

As such an outsider to the print world then, what prompted you to make a physical magazine in the first place?

Because it’s the only way that you can actually communicate a world anymore. When I was growing up, the online world was a separate world in and of itself. You could get lost. You could go for walks online. You could find digital communities that you could never, ever find IRL. Now the Internet is just this extremely corporate, platformatized desert.

When I have ten pieces of writing, I don't see why I would want to put it out on a website that someone is just checking in between Twitter and Instagram. I would much rather have these pieces physically printed and designed as their own world, so that a reader is receptive to it as a separate thing. Everyone's entire life is online right now, so having this physical object is a way of separating the magazine from that life. It's world building.

Heavy Traffic, Issue 6.