Photography by Torbjørn Rødland

Author

Jaja Hargreaves

Published

September 17, 2025

Torbjørn Rødland is a Norwegian-born, Los Angeles-based photographer celebrated for his uncanny ability to make the familiar both alluring and unsettling. His artistic journey began in his late teens, contributing illustrations and political cartoons to a local newspaper in Norway. This early experience cultivated his keen eye for composition and detail, which later translated into his photographic practice. Rødland’s work is marked by a disciplined embrace of formal clarity, even as he continually undermines surface legibility with unsettling details and wilful ambiguity.

His images routinely resist easy categorisation, straddling the boundaries between portraiture and still life, document and dream. His human subjects are often posed in ways that appear accidental or even awkward, frequently looking away from the camera, a reflection, he admits, of his own introverted stance towards the world. This approach invites viewers to linger in the act of seeing itself, rather than settling into the comfort of recognition or narrative.

Equally salient is his approach to objects and the everyday: oranges coated with human hair, Bolognese sauce inside a condom, or arrangements that take normality and twist it into forms charged with discomfort, play, or anxiety. For Rødland, these choices are neither random nor purely aesthetic. He describes a kind of attentiveness to objects that calls for psychological engagement: “If an object has something to tell me, it immediately grabs my attention.”

I’m an introverted observer, and this is how I experience the world.

You began your artistic journey as an editorial cartoonist in Norway. How did your early experiences with drawing and cartooning shape your later approach to photography?

It cemented my need for straight vertical lines and a preference for compositions that are formally clear and easily readable.

Has your Norwegian heritage and upbringing continued to influence your identity or worldview now that you live in the US?

Yes, you never truly outrun or replace your childhood or teenage years, but living at a distance offers a broader perspective.

Many of your human subjects are depicted in unusual poses, often not looking at the camera. What does this approach allow you to explore about identity and the photographic gaze?

I’m an introverted observer, and this is how I experience the world. This approach feels authentic to me.

Your still life work often features everyday objects presented in unfamiliar or even abject ways. How do you select and stage these objects to evoke psychological responses?

If an object has something to tell me, it immediately grabs my attention. I then spend time with it, exploring what or who it might need in order to reveal itself photographically with its full potential.

Photography by Torbjørn Rødland

It’s no secret, I depend on miraculous accidents.

When composing a shot, do you tend to meticulously control every detail, or do you embrace unexpected moments? Have you ever secretly hoped that a happy accident would take over and surprise you?

It’s no secret, I depend on miraculous accidents. It’s incredible what can happen in front of a camera when you’re both welcoming and prepared.

Is there an image you’ve made that you decided never to show? What made it too private, unresolved, or powerful to release?

Yes, there are a few strong photographs sitting on the sidelines. What am I waiting for? Perhaps it’s a context that allows for meaningful discourse around certain problematic motifs. I often insist that depiction does not equal endorsement, yet some viewers passionately disagree and challenge me with the “why do you manifest this negative behaviour?” kind of critique.

Are there private rituals or contradictions in your daily life that mirror the tensions in your photographs?

No, the tension arises from the subconscious, from the gods, if you will.

What’s the last thing that truly shocked you visually or emotionally?

A continuous stream of shocking AI-generated images, both still and moving, endlessly morphing.

What are you currently curious about or experimenting with in your practice, and are there any new directions you’re interested in pursuing?

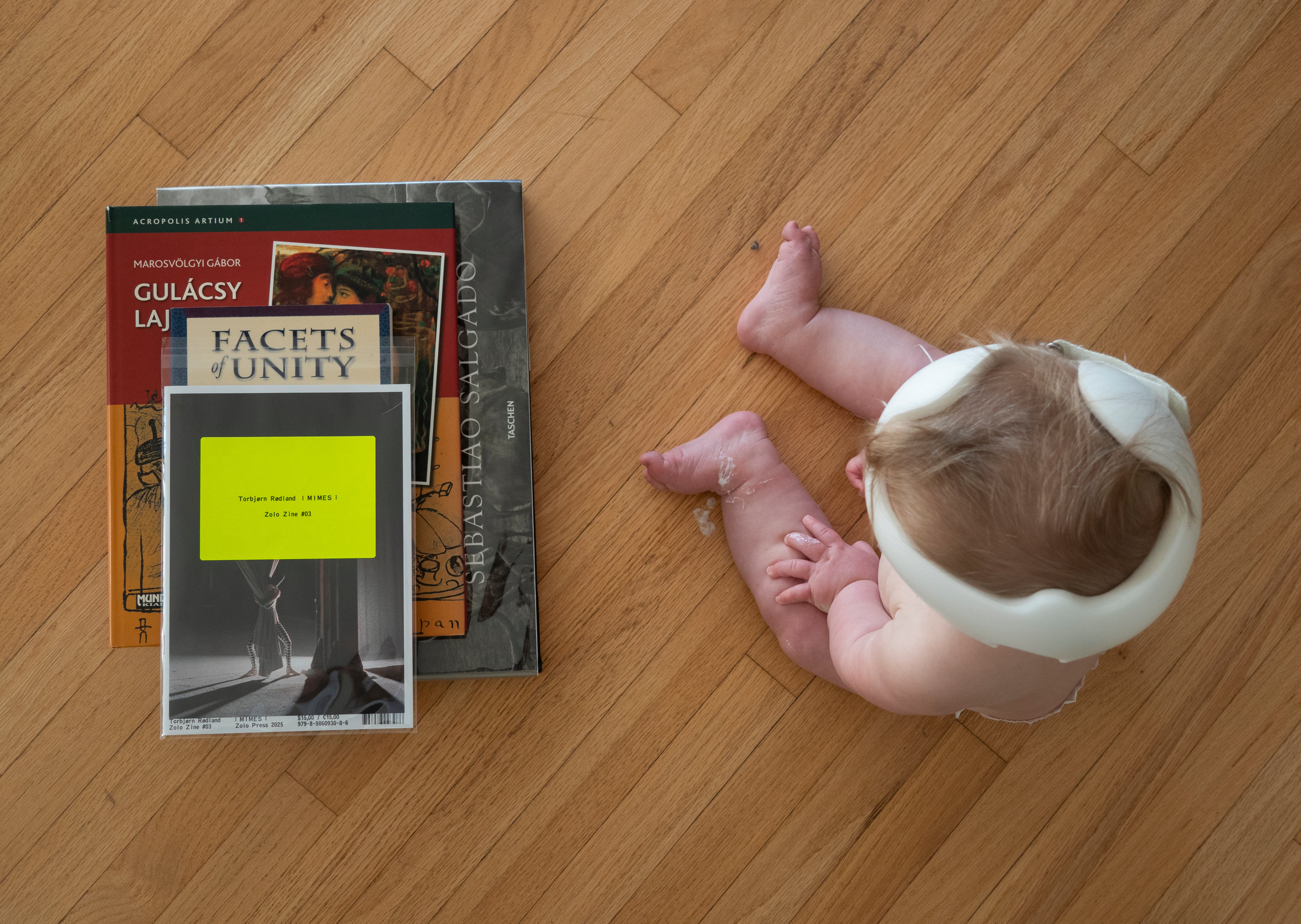

After thirty years of working with long lenses on large and medium format film cameras, I’m currently using a tiny mirrorless 35mm film camera with a wider fixed lens. The front and back covers of my new zine, Mimes, are created in this - what is, for me, a new photographic language. However, it is, of course, a very established language of the 20th century.

Photography by Torbjørn Rødland

Is there a recurring dream or image from your sleep that you’ve never been able to capture in your photography, but wish you could? What keeps it elusive?

Lately, I’ve been trying to depict the men in vividly coloured suits who lecture me about my shortcomings as a public speaker or figure. Yet, in my photographs, they end up feeling more like extensions of myself than the stern dream visitors who urge me to get my act together. What keeps them elusive? Emotionally, they remain alien to me.

Is there a particular book, film, or piece of music that you feel runs parallel to your photographic sensibility, even if it’s not directly related to visual art?

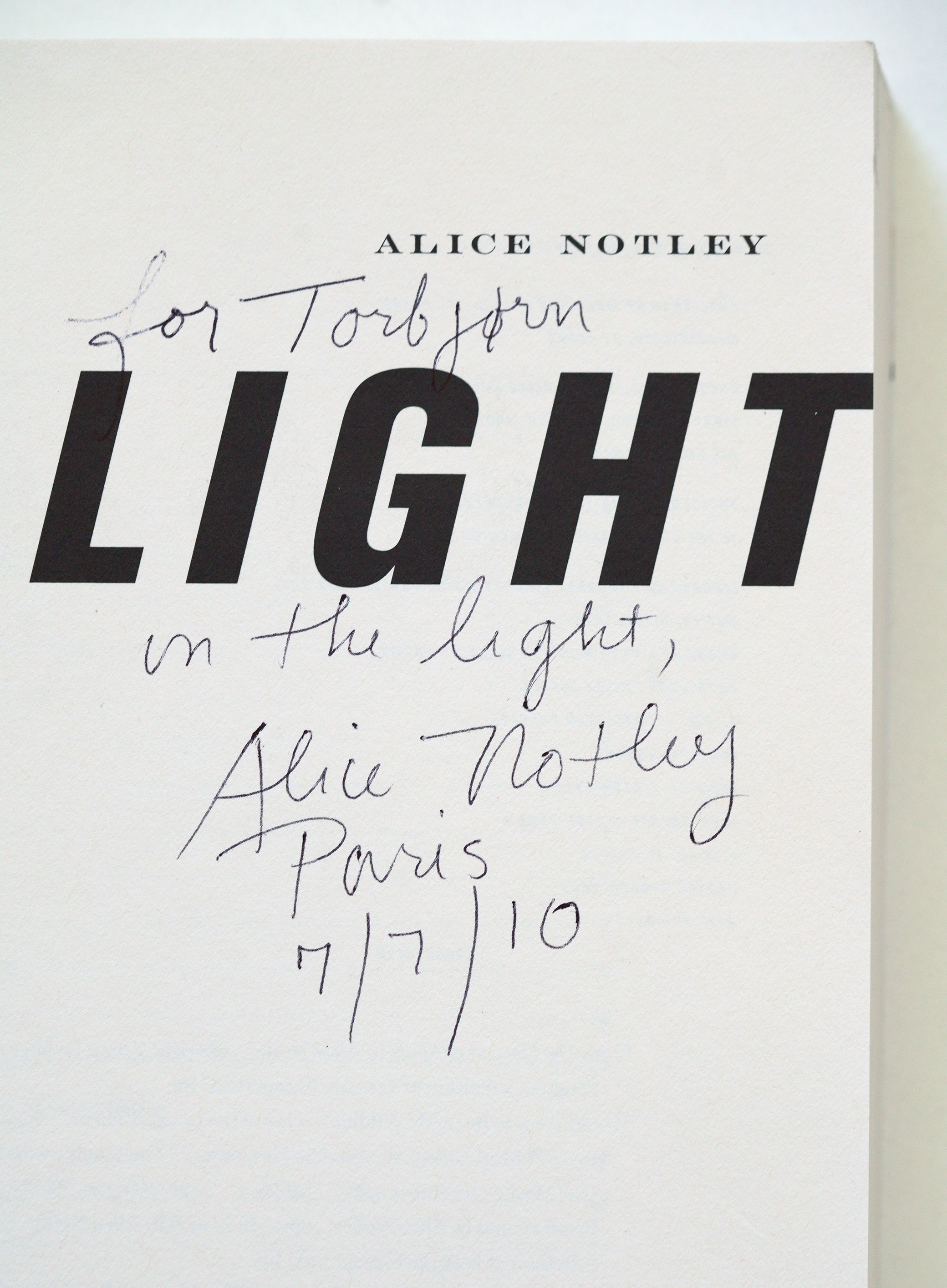

That’s a very good and difficult question. Since she passed away recently, I’m inclined to mention Alice Notley, and in particular her work The Descent of Alette. I’ve always found it fascinating to discover where an artistic project begins and what it strives to achieve. What resonates with me about Notley is her movement from an established pop culture sensibility toward ancient voices and symbols, a transformation from something light and fleeting to something deeply rooted. It’s a journey from the 20th-century consciousness of language into truly mysterious inner worlds.

Photography by Torbjørn Rødland

Her work appeared alongside some of your pieces, such as in The Touch That Made You, the 2017 exhibition at the Serpentine Gallery in London. Could you share how this collaboration came about? What was the process of bringing her poetry together with your images like for you?

I copied her address and number from an old phone book while staying in Paris during the latter half of 1999, a different world back then. Whenever I spent time in places like Tokyo in 2002 or Shanghai in 2003, I always carried one of her books with me, and I’d send her postcards - though not so many as to seem intrusive. This quiet connection ultimately led to us spending a day together in 2010, when I took her portrait. Seven years later, she wrote a poem for my Serpentine catalogue, and, more recently, another text for an upcoming book project of mine. I’d always assumed we’d make another portrait together. It’s hard to accept that some windows close permanently.

When you look back at your teenage self, what advice or message would you want to give him about art and life?

Study the Enneagram. Don’t just identify your type and set it aside. Truly delve into it and spend time understanding its deeper insights.

What have you discovered about yourself through studying the Enneagram more deeply?

It’s a very helpful tool for self-exploration and personal growth, but more importantly, it helps you see and better understand people who are different from yourself.