Published

December 15, 2025

Started by skater Charlie Davis in 2013, SkatePal has been an integral part of Palestine’s fledgling skate scene over the past decade. An informal project initially, partly inspired by the Skateistan initiative that started a year before, SkatePal has grown naturally over the years, but its original mission of supporting local skaters and their wider communities has remained steadfast.

“I studied Arabic, so I could speak the language quite well, and I'd been there enough to know my way culturally around the West Bank. I saw that there was an appetite for skateboarding in a place where there wasn't access for it, so I thought, ‘I might as well spend my time doing this,’” says Davis. “It wasn't my idea to turn this into a job or an organisation, but it just sort of became that way as it went on.”

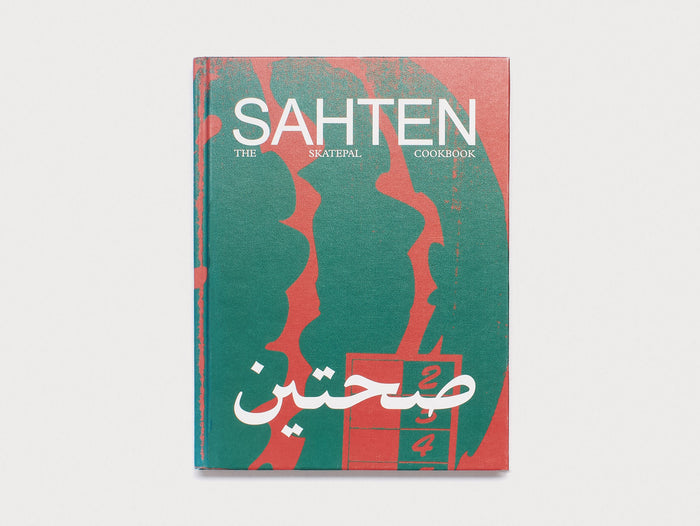

Developing a line of prints and apparel to help support what they do, SkatePal have also released several books: Sahteen, a cook book, as well as Haraka Baraka, an introduction to the Arabic language. A reflection of SkatePal’s community ethos, and its commitment to the people and culture of Palestine, Sahteen is a work of collaboration. It features recipes from local chefs and cooks alike, insights into skate culture, and even the illustrations are a team effort: local skaters helped colour each design in. Here Davis discusses community, skating and Palestine.

It was pretty low key in the beginning

SkatePal started in 2013. How did it come about in the first place?

I didn't start SkatePal as an organisation, initially it was a project that I’d wanted to do for a while. I had studied Arabic, I’d been to Palestine a number of times, and I had seen that although the kids there were really interested in skateboarding, there was nowhere to get boards. So after my degree, I got in touch with various youth centres to see who would be willing to host a skate camp and do some classes. At first it was me, my brother and a few volunteers. We began meeting people, met their families, and things grew a bit when there was more interest. For the first year, it was just about going there a few times, bringing some boards, doing some classes, and skating with the kids. It was pretty low key in the beginning, then the next year I established it as an organisation.

How do you feel it’s changed over the decade that it's been running?

At first it was me and one or two other volunteers, just doing classes in different locations around the country trying to raise the profile of skateboarding, and gradually we built a few more parks. We had international volunteers stationed there for maybe eight years or so, until 2023, and now all the classes and sessions are run by local skaters. We will still be involved in skatepark builds, and a lot of the overarching structural aspects of the skate scene, but we are focusing more on producing merchandise in our shops so we can raise enough money to cover all of our expenses. We’re moving into becoming more of a Community Interest Company that can support the local organisations who are doing the work on the ground. So that means us moving from it being me on the ground, to having internationals on the ground, to now just local skaters.

You can now say there's a bit of a scene

How has the scene changed in Palestine in that time?

At first there were only one or two people who had skateboards in the whole country that I knew about. As we started doing classes we were aware that a lot of the kids who got involved might only come for a few months, and then they wouldn't continue skateboarding, but that was fine because it meant we were still offering an outlet of a new sport to do. Over the years we’ve had a lot more uptake, and we’ve run regular sessions which really focus on getting an even split between boys and girls, because we're starting from zero, basically. There isn't a lot of the cultural baggage that you might associate with skateboarding in other parts of the world.

Early on, people came to the skate park to do sessions, but there wasn’t a lot of skateboarding in the streets. Now that there's been enough time for more local skaters to emerge, we’re seeing street skateboarding, and more the kind of skateboarding that we would see in the UK. It's really grown, you can now say there's a bit of a scene.

A cookbook is a timeless thing

How did the cookbook come about?

One of our volunteers, Tom Bird, came to us. He has experience of designing and making zines and other stuff, and he said, “I want to do a cookbook, because if we are producing merchandise it's nice to be able to showcase some of the aspects of the culture, language and people in Palestine, rather than just having a design which is divorced from any narrative in the context in which we're involved.” We said, “Yeah, sounds great.” And he basically did the whole project on his own, which became Sathen. It was really well received and is still popular today.

A cookbook is a timeless thing, it's never going to be not relevant. After the success of that, someone else in our team, Alex, came up with the idea of doing a book focused more on the language of Palestine, which led to Haraka Baraka. In both the books we wanted to interweave skateboarding, other aspects of skate culture, and the experiences of local and international skaters, in order to give people more of a flavour of what we do and what the skate scene is, and how close-knit a lot of the families and the volunteers are.

Sahten is also really collaborative. You have a lot of different recipes from different kitchens and different chefs, and even the illustrations have been coloured in by local skaters. It feels like every aspect has been thought about, in terms of bringing in as many people as possible.

It does have a very collective feel. I think it encapsulates what we try to imbue in the sessions and the work that we do, in that we try not to be too structured with anything that we do. It's more about being open and free, leaving space and seeing what happens.

Do you think the work you do has helped raise awareness of Palestine, both in terms of the ongoing occupation, and as a place that exists outside of the ongoing occupation?

I think so. We were aware that in the news people see Palestine, and it's always a negative story. We never hear a positive story, in the mainstream news anyway. People are just seen as facts in the news, you don't really hear about individuals. So being able to humanise the people there is quite crucial in order for the wider world to understand what's going on. We wanted to say, “Let's focus on skateboarding, and what people skateboarding are doing.”